Peaceful War

PEACEFUL WAR

How the Chinese Dream and the American Destiny Create a Pacific New World Order

DESCRIPTION

Peaceful War is an epic analysis of the unfolding drama between the inevitable forces of the Chinese dream and the American destiny. Just as the American experiment evolved, Deng Xiaoping’s China has been using “Hamiltonian means to Jeffersonian ends” to capture the American Dream, which was recently reinvented by President Xi Jinping as the Chinese dream to continue Deng’s new experiment. With a possible “fiscal cliff” in America and a “social cliff” in China, the author explores the history of Sino-American relations to see the future prospects: that Beijing and Washington shall return to their long-forgotten love affair in trade-for-peace era and eventually create a pacific New World Order with President Barack Obama’s Asia pivot strategy and the new Silk Road plan of President Xi. The key question is: will China in time develop into a democratic nation by rewriting the American Dream in Chinese characters, and how?

Peaceful War is an epic analysis of the unfolding drama between the inevitable forces of the Chinese dream and the American destiny. Just as the American experiment evolved, Deng Xiaoping’s China has been using “Hamiltonian means to Jeffersonian ends” to capture the American Dream, which was recently reinvented by President Xi Jinping as the Chinese dream to continue Deng’s new experiment. With a possible “fiscal cliff” in America and a “social cliff” in China, the author explores the history of Sino-American relations to see the future prospects: that Beijing and Washington shall return to their long-forgotten love affair in trade-for-peace era and eventually create a pacific New World Order with President Barack Obama’s Asia pivot strategy and the new Silk Road plan of President Xi. The key question is: will China in time develop into a democratic nation by rewriting the American Dream in Chinese characters, and how?

CONTENTS

Figures

Foreword by Jack Goldstone

Prologue: Sino-American Relations

A Sino-American Journey

Part One: Pacific Renaissance

1. The American Dream in China

Part Two: Nature’s God and the Mandate of Heaven

2. One Vision, Two Philosophies

3. From the Forbidden City to the Federal City

Part Three: The Great Drama in the Indo-Pacific Region

4. China’s Manifest Destiny in the Indian Ocean

5. The Ménluó Doctrine and the Asia Pivot Policy

6. The String of Pearls and the Colombo Consensus

Part Four: Chinese Destiny in America

7. Birth of a Pacific New World Order

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

Author

Praise

THE AUTHOR

Patrick Mendis is a distinguished senior fellow and an affiliate professor of public and international affairs at George Mason University’s School of Public Policy. He also serves as a distinguished visiting professor of international relations at the Center for American Studies in the Guangdong University of Foreign Studies in Guangzhou, China. An alumnus of the Harvard Kennedy School of Government and the Humphrey School of Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota, Dr. Mendis has worked for the U.S. Departments of Agriculture, Defense, Energy, and State as well as the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee, the World Bank, and the United Nations. He is a commissioner of the U.S. National Commission for UNESCO, an advisor to Harvard International Review, and a fellow of the World Academy of Art and Science.

Patrick Mendis is a distinguished senior fellow and an affiliate professor of public and international affairs at George Mason University’s School of Public Policy. He also serves as a distinguished visiting professor of international relations at the Center for American Studies in the Guangdong University of Foreign Studies in Guangzhou, China. An alumnus of the Harvard Kennedy School of Government and the Humphrey School of Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota, Dr. Mendis has worked for the U.S. Departments of Agriculture, Defense, Energy, and State as well as the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee, the World Bank, and the United Nations. He is a commissioner of the U.S. National Commission for UNESCO, an advisor to Harvard International Review, and a fellow of the World Academy of Art and Science.

AUTHOR’S PROLOGUE

A Sino-American Journey

Yes I am [a Hindu]. I am also a Christian, a Muslim, a Buddhist, and a Jew. ~ Mahatma Gandhi

Three years before President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, I was born into a family of a Buddhist mother and a Catholic father in the medieval capital city of Polonnaruwa in Sri Lanka, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. My long journey to America began—at least in my mind—when Peace Corps volunteers and 4-H exchange students visited my paternal grandparents’ three-acre rice field. One volunteer, a Catholic from Iowa, showed me a photo of the youthful American president who had established the Peace Corps. They were evidently inspired by Kennedy’s 1961 Inaugural Address:

To those peoples in the huts and villages of half the globe struggling to break the bonds of mass misery [here, the president was speaking about me], we pledge our best efforts to help them help themselves, for whatever period is required—not because the communists may be doing it, not because we seek their votes, but because it is right. If a free society cannot help the many who are poor, it cannot save the few who are rich.

For me, however, the most enduring impression was not the black-and-white photo of Kennedy but the free-spirited enthusiasm and sense of adventure exuded by these young goodwill ambassadors. Even though their stay was brief, the unrehearsed events—attending a Catholic mass, visiting a Buddhist temple, and playing with our water buffaloes in the rice field—were more than memories. They instilled an American dream in me: a dream that I might someday walk, talk, and think like them.

My American dream quickly dimmed when the socialist government came into power in 1970. Not only did the Madam Sirimavo Bandaranaike regime sever long-cherished U.S.-Sri Lanka relations overnight, but the world’s first woman prime minister also embraced Chairman Mao Zedong’s China. A year later on April 5—two days before my eleventh birthday—a youth insurgency broke out and political violence followed; a state of emergency was enforced. My introduction to socialism began with the infamous 1971 bloody revolt as I was compelled to wait in line for a loaf of rationed bread at the village cooperative store in the early hours of every morning.

The seven years that ensued were a life of economic austerity but I found solace in the free magazines and pictorials from China. The creation of a police and an army cadet corps (similar to Mao’s youth brigade, the Red Guard or the junior ROTC in the United States) was a blessing as I joined them to develop my discipline and patience—and craft a renewed purpose for my life. As my American dream subsided, I was captivated by the triumphs of Mao’s Cultural Revolution depicted colorfully in Chinese weeklies—a sort of propaganda. A new Chinese “dream” began to form, proving the ancient Confucian adage: “The grass must bend, when the wind blows across it.”

A LIFE OF PILGRIMAGE

This book is not about me; it is the worldview of an islander immersed in two cultures. As I do not have formal academic training (a PhD in Sino-American relations), I am obligated to tell the reader upfront of my scholastic deficiencies in comparative analysis. Throughout my formative years, however, I was not only fascinated by the culture, history, and geography of the United States and China but also studied their philosophies. Over the years, I have often been comparing and contrasting the American and Chinese political economy while traveling to all 50 states (and Guam and Puerto Rico) and the majority of the 34 provinces and special regions of China, including Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, and Tibet.

My active engagement in both cultures came with academic pursuits. First, my American dream was revived when I was selected to receive one of nine American Field Service (AFS) scholarships—out of over 100,000 applicants in Sri Lanka—to attend school in Minnesota in 1978. I learned to speak English there and graduated from high school in Perham, a rural resort town of 1,000 lakes similar to Garrison Keillor’s mythical Lake Woebegone in the “Land of 10,000 Lakes.” Second, after I completed two tours of teaching with American forces in the NATO and Pacific Commands of the Pentagon and before I joined the U.S. State Department, the University of Maryland offered me a visiting professorship in summer 2000 at Northwestern Polytechnic University in Xi’an, the earliest and best preserved capital of China. This urban center was once a melting pot of Muslims and other traders traveling to the starting point of the ancient Silk Road in central China. The walled city is now home to a world-renowned excavation of terracotta sculptures, depicting the warriors and horses of Shi Huangdi—the “first emperor” of China and the founder of the Qin dynasty (259–210 BC).

After returning from Xi’an, my interest in China lay dormant until I was doing research for my previous book, Commercial Providence: The Secret Destiny of the American Empire (2010). When I uncovered historical evidence that my birthplace of Polonnaruwa had long-term friendly relations with the Middle Kingdom, my attention was rekindled. The ancient royal city of Polonnaruwa reached its pinnacle under King Parakramabahu the Great (1123-1186), who unified the island under one rule. The king constructed an extensive irrigation system for this Buddhist city, and even sent successful expeditionary forces to India and Burma. Sri Lanka went to war with King Alaungsithu of Burma when the “commercial interests” of the maritime trade relations between the island’s great king and the powerful Khmer kingdom of Cambodia were threatened by the Burmese ruler. With a network of massive reservoirs and canal schemes (alongside Buddhist monasteries, public libraries, and other community work projects), King Parakramabahu launched an unparalleled agricultural revolution. His wise axiom, “Not even a little water that comes from the rain must flow into the ocean without being made useful to man,” revealed his dedication to building a hydraulic civilization and providing inspiration to the Green Revolution.

This meticulously engineered city was connected to the ancient Silk Road of the sea through the eastern port of Gokanna (which lies in a natural Trincomalee harbor also known as “China Bay”); agricultural surplus—mostly rice—sailed through the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea to the corners of Southeast Asia and the Middle Kingdom.8 In his History of Sri Lanka, Professor Kinsley De Silva writes:

Though most of the vessels used in her external trade were generally of foreign construction, sea-worthy craft were built in Sri Lanka as well, and are known to have sailed as far as China. Perhaps some of the latter may even have been used to transport Parakramabahu I’s troops to Burma.

During these years, commercial trade relations flourished. A century later, “swords and musical instruments were imported from China, and Chinese soldiers served in the king’s army” in the reign of Parakramabahu III, 1287-1293 (emphasis added). For me, the intricacy of this historic record provides an insightful context to understand the contemporary situation of Sri Lanka and its foreign relations with China and beyond.

In addition, the medieval Buddhist capital of Polonnaruwa also speaks to me spiritually. My paternal grandparents, who lived in a nearby village, adopted me when I was an infant and I grew up with them in a secluded Catholic environment where Christians were not always welcome by predominantly Buddhist population. My biological mother, a practicing Buddhist, decided to give me away before my first birthday for medical and astrological reasons. Entrepreneurial by nature, my grandfather was one of the early settlers who voluntarily moved from the west coast once colonized by the Portuguese to find new life in a recently-created colonization scheme designed to revive the ancient glory of the city’s agricultural economy. A small community of Christian rice farming settlers secretly attended a makeshift church, which was later known as the first “church” in Polonnaruwa. Built on a “small plot of land” donated by my grandfather, that church later became the Holy Rosary Church. During my determinative years, I attended a Buddhist public school and was influenced by Buddhist teachings, but weekends were always confined to church-related events and Bible studies. Thus, I have grown to identify myself as a “Catholic Buddhist:” a Christian by faith, a Buddhist by practice.

The confluence of Buddhist and Christian religious teachings led me to a vision of unity in everything and with everyone. The synchronized message of my Polonnaruwa narrative—both personal and global elements—later made the city famous in the English-speaking Christian world after Reverend Thomas Merton (1915-1968), a Christian mystic at Gethsemani Monastery in Kentucky, visited the medieval capital in 1968. The American Trappist monk later wrote that he had attained his enlightened “insights” and “total integration” with God when he was contemplating on a rock in front of three beautifully stone carved, larger-than-life figures of a meditating, standing, and reclining Buddha at Gal Vihara (“Rock Temple”) in this consecrated city. In a famous passage of his Asian Journal, the reverend wrote,

I am able to approach the Buddhas barefoot and undisturbed, my feet in wet grass, wet sand. Then the silence of the extraordinary faces. The great smiles. Huge and yet subtle. Filled with every possibility, questioning nothing, knowing everything, rejecting nothing, the peace not of emotional resignation but of sunyata” [emptiness].

The contemplative pilgrim concluded his journal with these words, “This is Asia in its purity, not covered over with garbage, Asian or European or American, and it is clear, pure, complete.” It is remarkable that while the place has long been a metropolis of ancient ruins, its stunning remnants provided the Catholic philosopher a new realm of intrinsic forces for God realization. His experience teaches us an important lesson on the nature of the integrative mind and the power of history to transcend religious, ethnic, racial, political, cultural, and other social boundaries in order to locate unity in diversity.

A SEARCH FOR INTEGRATION

In the final analysis, this book presents a triangulated framework of history, geography and philosophy to better understand the changing nature of the Sino-American relationship. In his book Archeology of Knowledge, French philosopher Michel Foucault convincingly explained that we need to compare and contrast several periods of history, different forms of connections, various level of hierarchies, numerous networks of determination, and altering levels of teleology (the study of causes in nature) to fully understand events and interpret evolving relationships. For me, history is the archaeology of the present and future because, as Foucault wrote, historically interpretive analysis gives meaning to the present state of knowledge of public policy and integrative thinking (from various disciplines) to create a more peaceful future.

The prism through which I analyzed the Sino-American bilateral relationship in the book emerged from the worldview of an islander, who is himself a very product of two seemingly opposed cultures, religious convictions, and political persuasions. I have felt not unlike Robinson Crusoe on a shipwrecked desert island, however; the writing of this book has always been a challenging, sleepless, and often lonely task for me (except on the occasions of my loving wife’s interruptions with green tea, sweet delights, and other enchantments). In the process, I have tried to bring a wide-angled look at history into the present policy dialogue in order to make sense out of the foreign policy decisions of our leaders and their strategies on both sides of the Pacific. I hope this worldview lights a candle for illuminated understanding of the world’s most important bilateral relationship.

In the initial draft of this book, I had purposefully selected nine quotations from among the fourteen inscribed on the National Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial in Washington, D.C., as epigraph at the beginning of each chapter. The prevailing copyright issues, however, prevented me from using them in the final manuscript. The twenty-eight feet (nine meters) high national monument is geometrically positioned on a four-acre (two hectares) site near the Tidal Basin between the Abraham Lincoln and Thomas Jefferson memorials. Facing the Jefferson memorial, the centerpiece of the tribute to the Civil Rights leader is nine feet taller (three meters) than the sculpture of Jefferson himself. The figure of Dr. King looks decisively back at Civil War President Lincoln’s monument, the site of the Baptist preacher’s historic “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963. In the midst of all of this lies a powerful but subtle message on American history and national identity as Dr. King stands at a mid-way point, looking ahead into a world of Jeffersonian ideas and ideals. Jefferson, who kept African-American slaves and fathered children with Sally Heming (a slave), was a complex Founding Father who lived a life of contradictions.16 President George Washington’s namesake capital, once a marketplace for slave auctions, is now synonymous with democracy and freedom; so is the iconic Jefferson, who wanted to build an “Empire of Liberty” for the world.

The statue of Dr. King’s upright figure faces the dome of the Jefferson memorial as if the Nobel Peace Laureate were still inspired by the author who defined the essence of “American Dream” as emanating from “life, liberty, and the pursuit of [spiritual] happiness.” Believing in this Jeffersonian vision, King advanced American ideals in practice and asked for human judgment to fall on individual character—not race, color, or background. The selection of a mainland Chinese artist named Lei Yixin (as opposed to an African-American) to carve the granite sculpture of the Civil Rights leader further reaffirmed what America represents as a global nation. Born to a family of scholars in Changsha, the capital of Hunan province, Lei was one of millions of “educated youth” sent to the countryside during the Cultural Revolution; after designing giant monuments of Chairman Mao, a leader who wanted to create a country of free from the “bourgeoisie” classes to achieve a socialist dream of equality and prosperity for the “proletariat” class, the artist then received the commission to sculpt the American messenger of peace and mutual respect.

Like many of the other national monument projects—such as the Vietnam veterans memorial designed by Chinese-American Maya Lin and the Statue of Liberty in New York harbor gifted by French Freemasons—King’s memorial foundation also attracted opposition, particularly after “the Chinese government [decided] to give $25 million to the King memorial fund.”19 In the end, China’s economic diplomacy prevailed and the project went forward. Chinese involvement in an American project that championed the indomitable human spirit recalled the Civil Rights leader himself, who was essentially protesting human rights violations within the United States. The message—just like in my book—is that Jeffersonian democratic ends will only be achieved through Hamiltonian economic means (similar to that of Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs). While China focuses on accomplishing the latter, King’s words still resonate with Chinese citizens and their government as they were playing Barack Obama’s 2008 “Yes, We Can” speech everywhere. Lei, who met the memorial foundation president in charge of the King’s project at a sculpting workshop in St. Paul, Minnesota, said, “Dr. King’s vision is still living, in our minds; we still miss him, we still need him.”

The master artist may not share the same sentiments toward his most famous countryman from Hunan province, as it was Chinese economic reformer Deng Xiaoping—not Chairman Mao—who took China down the American pathway of Hamiltonian means to pursue Jeffersonian ends. As Dr. King’s posterity is carried forward through a mainland Chinese artist, the United States is reasserting its founding vision (i.e., the “American Dream”) as a force for good and unity; the coining of the phrase “Chinese dream” by President Xi Jinping is just a beginning for “One World, One Dream,” the triumphant 2008 Olympic slogan in Beijing.

WELCOME NOTES TO READERS

Finally, I would like to note that the years before and after the Christian era are denoted AD (Anno Domini) and BC (Before Christ); whenever the years are not explicitly identified, they refer to AD. There is another minor note that the native English readers may already know: the generally accepted standard that the year 2 AD, for example, is actually 1 year after Jesus Christ was born; therefore, when I write the “twentieth century” phrase, for instance, I am referring to the years from 1900 to 1999.

Chinese words and names like Mao Tse-tung and Fa-hsien are spelled according to the pinyin system of modern China (Mao Zedong and Faxian). Linguistic scholars often agree that the pronunciation is closer to actual native speakers of Chinese. To avoid confusion, I have used the pinyin system throughout the book, except in certain occasions when deemed proper to be pedantically precise for clarity. Other words are spelled in a way that associates them more to the general usage of Confucian Chinese mainlanders than to Hong Kong islanders and the English-speaking world; for example, the word like “Taoism” seems dated, so I have employed “Daoism” (except in direct quotations) to reflect the preferences closely connected with Beijing.

In conclusion, as a life-long learner and a visitor to over one-hundred and five countries, I would like to invite you to share your reflections and worldviews to help me understand alternative perspectives to see the world differently. It is expected and even welcome to encounter a wide range of responses; if my village in Polonnaruwa has 10 readers, there will be 100 interpretations!

See the Amazon page’s Click to Look Inside.

REVIEWS

PEACEFUL WAR

How the Chinese Dream and the American Destiny Create a Pacific New World Order

“No international strategic relationship is more important or more consequential than that between the United States and China—now and as far as we can reasonably see into the future. . . . Anyone seeking a holistic understanding of the Sino-U.S. relationship—and where it might be heading—should read this book.” —CIA Director JOHN MCLAUGHLIN, former acting director of the Central Intelligence Agency

“Luminously situated President Obama’s Asia pivot . . . in a rich historical context . . . that is often lost in geopolitical writing” —Senator THOMAS DASCHLE, former U.S. Senate Majority Leader

“Luminously situated President Obama’s Asia pivot . . . in a rich historical context . . . that is often lost in geopolitical writing” —Senator THOMAS DASCHLE, former U.S. Senate Majority Leader

“Another landmark work comparing Chinese and American national discourses and the future of their relations.” —Professor SHEN DINGLI, Fudan University

“Meticulously researched, this unprecedented study of the evolving Sino-American relations is timely, levelheaded, and fair above all else.” —HARVARD INTERNATIONAL REVIEW

“A dazzling analysis, full of history, philosophy, ironic similarities and unusual distinctions, fears and hopes, but mostly dreams—the kind of dreams Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Nelson Mandela dreamed. For that reason and more, Peaceful War is worth reading.” —Colonel LAWRENCE WILKERSON, former chief of staff to U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell

“An innovative analysis that is wise, welcome, and timely.” —Dr. WEI HONGXIA, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences

“[This book] is a breakthrough that is powerful, inspiring, and visionary. . . . the world should read this book and heed Dr. Mendis’ wise counsel.” —Professor WANG DONG, Peking University

“Dr. Mendis brings all students of international relations into a long journey of rational soul searching.” —Professor ALEXANDER HUANG, Tamkang University

“The highest compliment a reader can give an author is to think: ‘I wish I’d said that.’ This imaginative and optimistic book provokes numerous responses of this sort. Mendis counsels historical awareness, cultural sensitivity, and humility as Americans peer across the Pacific to a China intent upon assuming its rightful place in the world. It’s hard to think of better advice.” —Dr. ROBERT HATHAWAY, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars

An important book that changes the way we think about these two superpowers.” —Dr. SHIRO ARMSTRONG, Australian National University

“A naturalized U.S. citizen, Professor Patrick Mendis . . . is himself an authentic American message to Asia.” —Professor TANG XIAOSONG, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies

“Innovative work . . . to elucidate some of the compelling internal challenges that lie ahead for the government and the people of China.” —Professor ERIC SCHWARTZ, former U.S. Assistant Secretary of State

A keen analyst, a creative thinker, and a precise writer . . . to guide the Sino-American relationship.” —Ambassador SHAUN DONNELLY, Vice President of the U.S. Council for International Business

“Unique perspective and wide-angled vision.” —Ambassador JAYANTHA DHANAPALA President of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs

“A delightful glimpse into the future.” —Professor NIU MEILI, Sun Yat-sen University

“Engaging book.” —Dr. PARAG KHANNA, author of How to Run the World

“Mendis’ book . . . both nations could learn to appreciate each other better.” —Professor CHUANJIE ZHANG, Tsinghua University

“An intriguing and fascinating study.” —Dr. NIKLAS SWANSTRÖM, Director of the Institute for Security and Development Study, Stockholm

“This book is an important guide for broader policy dialogue among strategic thinkers in both Beijing and Washington.” —Professor EDWARD RHODES, George Mason University

Peaceful War

Peaceful War

Commercial Providence

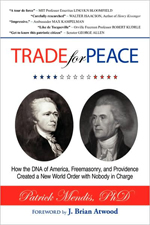

Commercial Providence Trade for Peace

Trade for Peace

Glocalization

Glocalization